To read | Hard drives and somewhat volatile memories : what constitute today’s musical heritage ?

- Adrien Durand

Visions

As I started immersing myself in the independent music world and in underground scenes, I was quickly stunned to find out how many people lived, paid rent, and supported their artist bohemian lifestyle thanks to intergenerational wealth. If I’ve learned to no longer rely on the state of a musician’s track pants or fanny pack to guess their social status, I’ve often wondered what kind of inheritance I, as a child of the precarious lower middle class fairly opposed to materialistic and careerist ideologies, would be able to leave to my children.

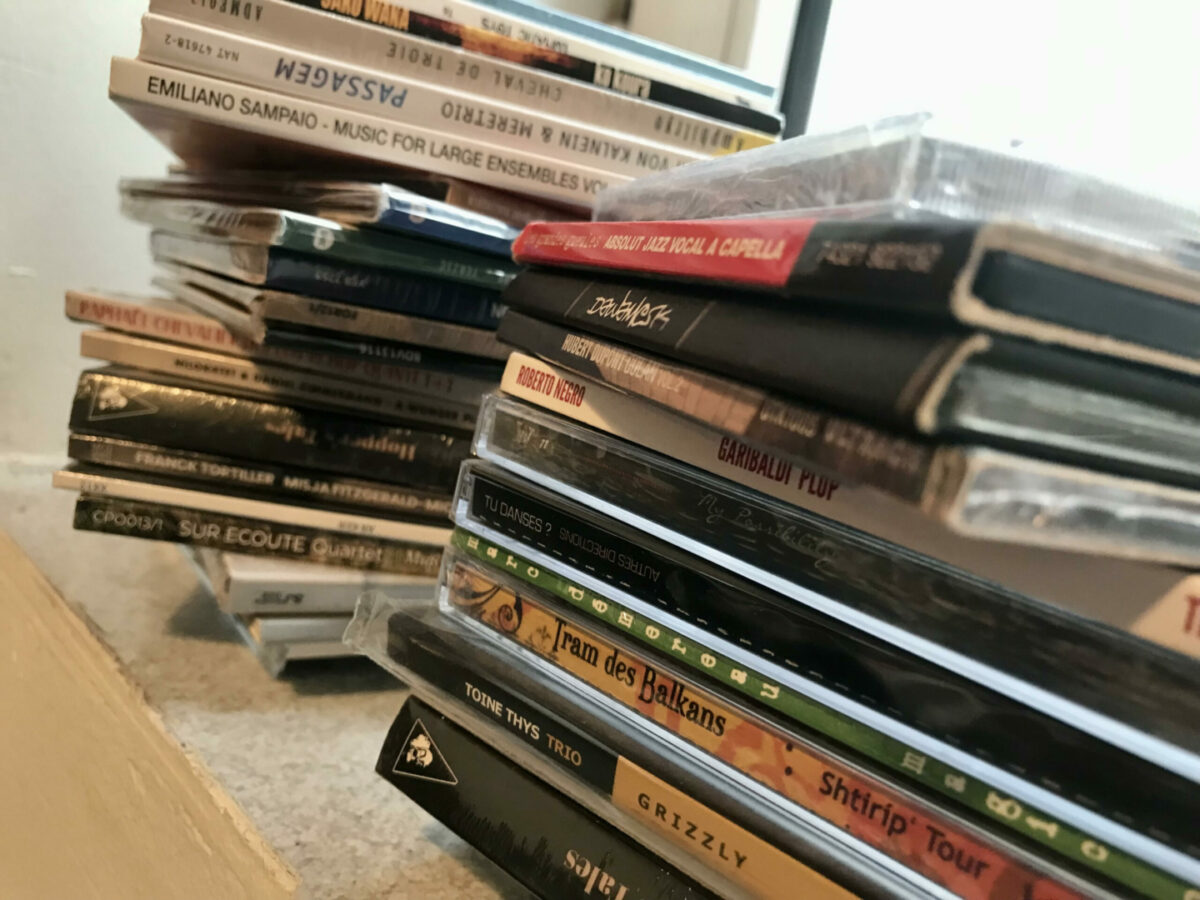

Looking around, seating in my living room faced with existential angst, it was obvious: my records, books, and musical instruments accumulated one way or another over the years, but that at least held some value in my eyes – that of embodying the journey of my aesthetic emotions. But time passed and I had to kick a first record collection to the curb, re-sell some instruments and stop buying records once they passed the 30-euro mark. What then, was I going to leave to my beneficiaries?

The ideal counterargument is obvious: digitalization ensures that we won’t be losing anything anymore, that we can keep it all, that we can always have handy the (almost) entirety of the world’s musical production (and therefore, of its memories). If digital neo-capitalism managed to make us believe one thing, it is that satisfaction is only found in accumulation.

But here’s the catch, human memory is no RAM, the brain is not a cloud, and a Spotify library is hardly a record collection (which includes your high-school ripped cds, various mixtapes, harsh noise tapes devoid of mastering, and demos of your clumsy post-hardcore band). And the fact that Spotify (and Adele) started selling vinyl records (just like Amazon opened brick-and-mortar libraries in the Unites States) goes to show that Big Tech is well aware of the state of affairs. It’s a funny paradox to see the tenors of digitalization cling on to artifacts.

A rather unexpected consequence of this content globalization is the erasure of local defining features.

At this point, rather than falling into a slightly abstruse, bitter nostalgia, I prefer considering this unprecedented fight between physical and digital cultures as a Holy Grail of sort: our affectivity. Is a world where algorithms have slowly eaten away at record clerks and music journalists’ recommendations necessarily bad? If this question would probably require its own article, maybe even a book, the fact remains that this permanent influx of cultural content designed to appeal to us creates a type of widespread and somewhat stunning erosion of critical thinking. In a space-time continuum where all concepts of chance, negative appreciation and rupture have been erased in favour of the illusion of permanent contentment and satiety (who said clientelism?) how much room is there left for our strolls, our aesthetic wanderings, the collisions between musical movements and History’s futile moments? Not a whole lot, you must agree. It’s probably why each year streaming platforms push the humanization and socialization of their tools even further, from your “year-in-review” to your “most played songs of 2021”, thus attempting to make us believe that our analog human memory (for lack of a better word) is stored on a server cooling down somewhere in a fiscal paradise. In other words, digital platforms are trying to turn abstract events of our online lives into something concrete and tangible, to create the illusion that we need them to record the most important moments of our existence (such as songs, for example).

I talked about it a few years ago during an interview with Ron Morelli, founder of techno label (in the broadest sense) LIES, who was lamenting some kind of loss of meaning. To him, newer labels were only picking music off the internet, without even meeting the artists or trying to defend a context and a community of kindred spirits, unlike models such as Dischord in Washington, DC, or Downwards in Birmingham, who were defending an anchoring in a local community. This brings us back to this feeling of air-sea fluxes, often disturbing to anyone who experienced the 20th century and modems that beeped when turning on. How, then, can we build a durable musical memory and a tangible heritage, in this endless open bar? Well, probably through the most real musical experience that remains: live shows.

Even if mobile phones are often omnipresent and that social media platforms play their role as disturbers, we must admit that just like watching a movie in theaters, live music remains one of the last strongholds soliciting our attention for a duration exceeding 2 minutes 30.

It is precisely there that a three-party schema conducive to making a lasting impression unfolds, unhindered: a geographic location, a musician, and someone attending the performance.

In this regard, music venues remain bastions of a musical experience that truly holds meaning, in the way that it gives a platform to a tangible flux, admittedly fleeting but that creates a lasting memory in our mind (depending on our relationship to some relaxing substances, of course). At a time when purchasing a record has become a real luxury, and when each Friday, kilometers of new music are unleashed without us being able to really judge whether we are completely missing out on our desires, continuing to attend shows and festivals allows us to reconnect with the essence of our aesthetic emotions. So, what will you leave to your children? An oral recollection of your live music experiences, and let’s hope, the desire to follow in your footsteps by imprinting fleeting days in the dark chamber that is your memory.

This article was published in the second edition of Périscope Magazine Creative Spaces for Innovative Music, published during the European project Offbeat.

Find the entire selection of article on the page Europe

View the digital copy of the magazine here

Please get in touch with us if you would like to receive a copy periscope.communication@gmail.com